The Nature of Content: New York Times vs Netflix

How does the nature of content impact long-term margins at media businesses? All else equal, the more durable your content, the less you need to continually spend on content creation. Let's explore that.

Summary:

All else equal, the more durable your content, the less you need to continually spend on content creation.

Intro:

Most people find it easy to draw parallels between Netflix and Spotify: Netflix provides streaming video on demand and Spotify provides streaming audio on demand.

While comparing Netflix and Spotify is indeed an interesting exercise, I think that the New York Times is a better comparison for Netflix.

Netflix’s main Power is economies of scale in content creation, which is a core Power of the NYT, too. This is not the case for Spotify yet (SPOT is an excellent business with enduring competitive advantages, but Spotify does not have economies of scale in content creation today).

This is the first in a series of posts comparing and contrasting the NYT to Netflix.

In this post I focus on the nature of video vs news content, and what impact this has on long-term margin potential. I ignore the NYT’s advertising business as well as its print subscription business since those revenue lines are less relevant to the NYT today and are beyond the scope of this post.

Outline for the rest of this post:

- Back-to-Basics – what do Durability, Excludability and Rivalry mean in economics?

- Content Durability/Excludability/Rivalry at the NYT vs NFLX

- How does this impact long-term margin potential?

- Appendix – adding in Spotify and Disney+

1: Back-to-Basics – what do Durability, Excludability, and Rivalry mean in economics?

Wikipedia has an excellent page summarizing these economic concepts. Think of them each as a continuum, where different goods fall at various points along the continuum.

Rivalry[i]:

A good is rivalrous if its consumption by one consumer prevents simultaneous consumption by other consumers.

Examples of rivalrous goods include domain names, tennis racquets, and spaghetti (unless you’re Lady & the Tramp).

In contrast, non-rivalrous goods may be consumed by one consumer without preventing simultaneous consumption by another consumer. A good is non-rivalrous if the cost of providing it to an incremental individual is zero (this doesn’t mean that its total production costs are zero, just that incremental production costs are). Most non-rivalrous goods are intangible.

Examples include software (e.g. iOS/Windows), a painting/scenic view, and clean air.

Durability:

A hammer is a rivalrous, durable good: person A using a hammer means that person B cannot use the same hammer at the same time (i.e., the hammer is rivalrous), however after person A is done using the hammer person B can then use it. While it can’t be used by persons A & B simultaneously, person A does not “use up” the hammer. The hammer is durable through time.

In contrast, an apple is a rivalrous, nondurable good: once person A eats an apple, it is “used up” and cannot be eaten by person B. An apple is not durable through time – it either rots or is eaten.

Excludability:

A good or service is excludable if it is possible to prevent consumers who have not paid for it from having access to it.

For example, free-to-air television is non-excludable, whereas movie showings in a cinema are excludable.

2: Content Durability/Excludability/Rivalry at the NYT vs NFLX:

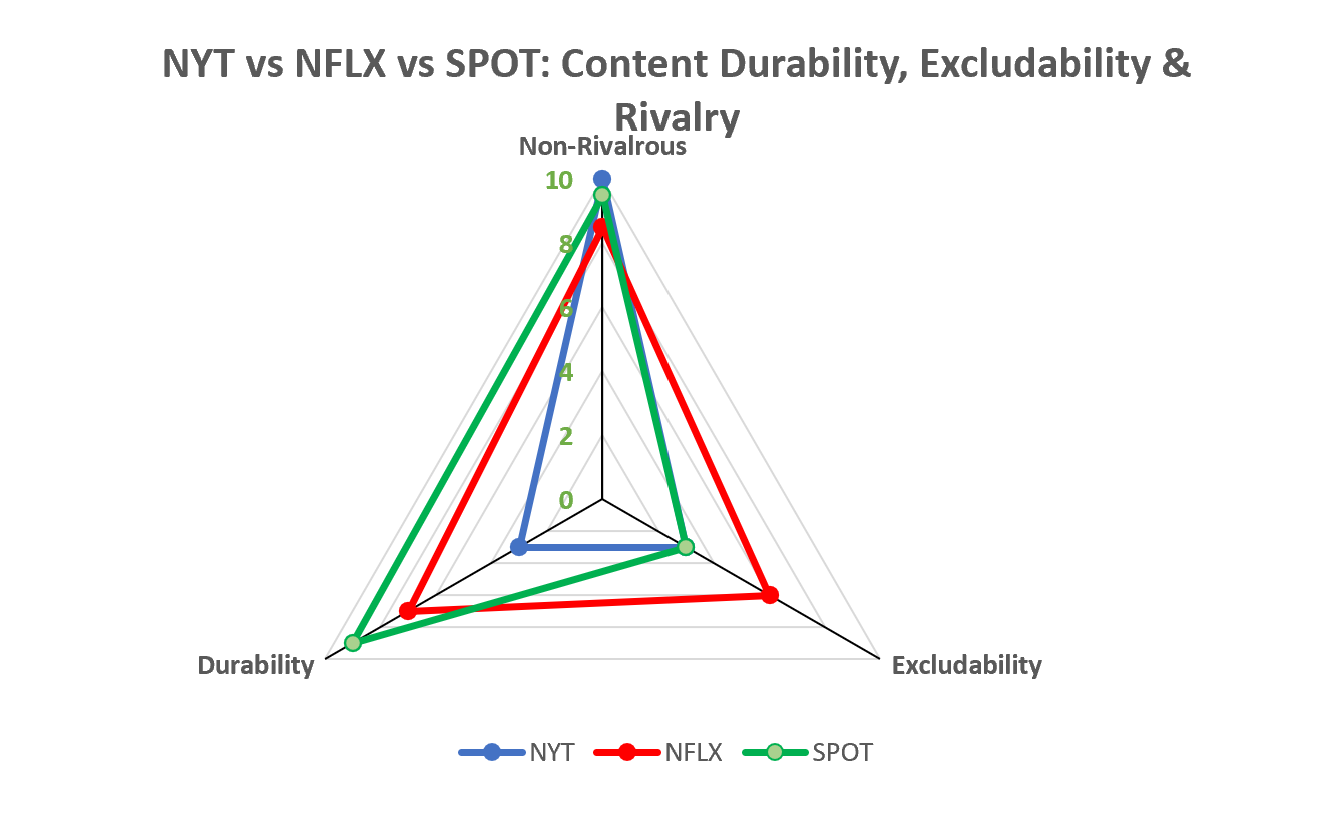

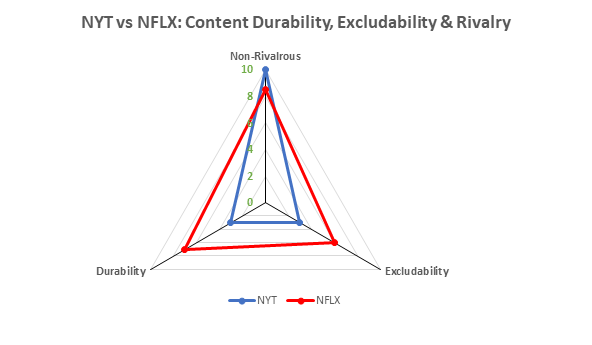

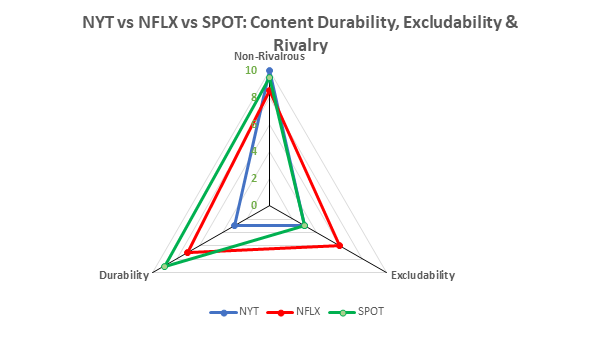

(Not precisely to scale…)

Durability:

NFLX’s content is much more durable than the NYT’s. While consumption of an article does not ‘use-up’ the article, time erodes most articles’ relevance and thus their value to a greater degree than for a Netflix show.

The main difference between video content at Netflix and news content at the NYT is that, along a scale of ‘ever-current’ to ‘evergreen’, Netflix is much closer to evergreen and the NYT is much closer to ever-current.

Someone subscribing to Netflix today would be attracted by the entire backlog of content. The first season of House of Cards is just as relevant and enjoyable for a first-time viewer today as it was in 2012. Same thing for Orange is the New Black, Stranger Things, and even Tiger King. Hit shows are likely to be just as enjoyable in 2030 as they are today.

On the other hand, people do not tend to subscribe to the NYT for the content from 2012. The NYT produces many exceptional investigative journalism pieces that will stand the test of time, but even these pieces tend to lose their relevance faster than a television show like Friends.

Excludability:

Netflix does not have a monopoly on video content creation any more than the NYT has a monopoly on news. However, Netflix’s content is more excludable than the NYT’s because news stories themselves are typically non-excludable (coverage of the presidential election is not exclusive to the NYT, for example). In contrast, much of Netflix’s content is original or licensed content that can only be viewed on Netflix. On a spectrum of excludable to non-excludable, Netflix sits much further towards excludability than the NYT does, even though the NYT has unique opinion and analysis content.

Rivalry:

Both Netflix and the NYT’s digital subscriptions have non-rivalrous products in terms of having (close to) zero marginal cost in serving each additional customer. Consumption of a NYT article by one subscriber does not prevent another subscriber from reading it at the same moment. The same is true for shows on Netflix, however the additional bandwidth requirements for streaming video content mean that video is more rivalrous than news articles.

3: How does this impact long-term margin potential?

The main difference between the New York Times and Netflix is that Netflix’s content is more durable through time. This has important repercussions for the long-term margins that these businesses can generate.

For example, it’s possible to imagine a situation where in 2035 Netflix has created content at a much faster rate than subscribers can view it and thus where Netflix has generated a ‘content surplus’ i.e. where viewers have such a large backlog of content to work through/re-watch that Netflix could conceivably ‘turn-off’ its content creation for a while and generate massive FCF.

It’s impossible to imagine the same for the NYT. The NYT has to perpetually ‘feed the beast’ to provide the service that consumers subscribe for (feeling informed on current events). The NYT must re-earn their brand by creating great content every single day. At scale, Netflix might not have to.

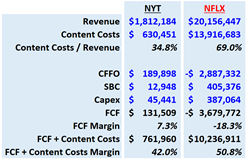

The table below demonstrates the impact this would have on free cash flow margins at each business if they were to stop spending on content creation entirely and did not see any corresponding drop in revenue. This is not feasible for either business today, nor will it ever be for the NYT. It’s worth considering for Netflix, however, as a thought experiment. Figures from 2019:

This table shows that Netflix would already be at 50% FCF margins today if they were able to stop spending on content creation. Obviously they are a long way away from that, but it serves the point that as Netflix increases its content (and generates a ‘content surplus’ from creating more content than consumers can consume over a period of time) it can generate increasingly attractive FCF margins. Of course, all of this is predicated on Netflix ‘getting there’ in terms of creating that content surplus, and then being able to sustain it!!!

4: Appendix – adding in Disney+ and Spotify

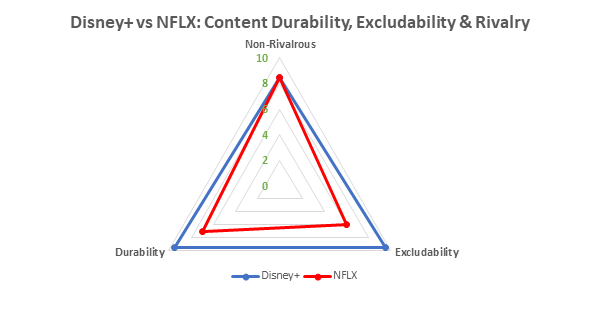

It’s fun to compare Netflix to Disney+:

Disney+ also has more durable content. For example, Cinderella is >70 years old and its graphics are sub-par by today’s standards, but the movie still stands the test of time. In contrast, Netflix’s Tiger King was a phenomenal Netflix original but seems unlikely to be a docuseries that we’ll be introducing our great grandchildren to in 2090 – it is unlikely to be culturally relevant even if it is still technically “durable” (i.e. the video will still play, etc).

This is an important reflection of Netflix & Disney’s respective strategies: Netflix is primarily playing the economies of scale game where it makes sense to churn out as much content as possible, whereas Disney is primarily playing the brand game where it makes sense to spend more time creating only extremely high quality movies (& shows) that will stand the test of time.

Doing the same chart with Spotify:

In its current form, Spotify has:

- More non-rivalrous content than Netflix (bandwidth requirements for streaming audio are lower than for video)

- Less excludability (other than their exclusive podcast deals Spotify has virtually no exclusive content – music is universal)

- Greater durability (since songs from the sixties do not sound materially different in audio quality to current songs in the same way that movies from the sixties look very different to current movies)

Spotify has the potential to generate very high margin revenue elsewhere, but it is unlikely to ever be in content creation (other than perhaps through podcasts). This is largely intentional: music artists don’t want exclusivity – they want the greatest reach possible so they can make as much money from touring as possible. The Great Lockdown may change that but only time will tell.

As I’ll explain in a future post, having no exclusive music content is an advantage for Spotify in many ways. Just don’t expect Spotify’s competitive advantages to be in leveraging the fixed cost of content creation like it is for NFLX – Netflix is the wrong business model and competitive advantage analogy to use when thinking about Spotify!

[i] Most non-rivalrous goods are only non-rival up to a point: the internet is non-rivalrous but a high density of users decreases available bandwidth and increases latency for users; public roads are non-rivalrous until they become too congested; the Mona Lisa is non-rivalrous until the crowd of selfie-taking-millennials blocks an incremental viewer’s line of sight. Note that there are anti-rivalrous goods, too (where the more that people share the good, the more utility each person receives in consuming it). Anti-rivalrous goods typically result in network effects. For anti-rivalrous goods, consumer “n+1000” enjoys a better experience than did customer “n” –directly as a function of adding 1000 more participants to the market. The English language is anti-rivalrous, for example.